Does brain structure determine your political views?

- Published

Politics is one of the most complex areas of human thought. So when I heard the claim that scanning people's brains could predict political choices, I was naturally sceptical.

Brain science is achieving extraordinary insights, but mapping what you can measure in a brain scanner on to human social interactions is a huge leap, like trying to find exact correlations between two bowls of soup - only one soup is made from vegetables, macaroni and stock, and the other soup is made up of abstract ideas like economics, equality and history.

But in the US and in Britain, psychologists and neuroscientists are doing serious research into linking political attitudes to what goes on inside our skulls.

"By looking at how the brain is processing political phenomena, we can understand a little better why we're doing what we're doing," says Darren Schreiber, of Exeter University.

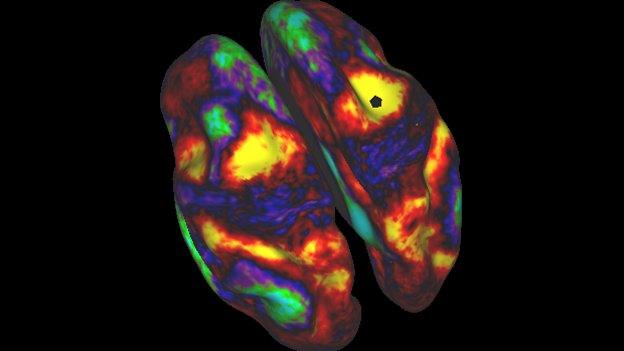

He started using fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) while in America, to look at patterns of activity in the brain when people made decisions, especially those involving risk.

While their decisions weren't all that different, Dr Schreiber saw variation in the parts of the brain that were most active in self-described conservatives and those who called themselves liberal.

He won't generalise about exactly how conservatives and liberals think, but he does think his work suggests that differing political outlooks reflect deep-seated divergence in how we understand the world.

Neuroscientist Read Montague, of University College London and Virginia Tech, was sceptical when approached to help political scientists with their research.

"I laughed them out of the room," he says. But when John Hibbing and his team at the University of Nebraska showed him their data he changed his tune.

Their studies of twins suggested that political allegiance was partly genetic.

Not as strongly as height, for example, but enough to suggest that some people really could be dyed-in-the-wool conservatives - or dyed-in-the-DNA, at least.

But how, exactly, could genetic differences be expressed as political differences in the real world?

Dr Hibbing and Dr Montague wanted to know if these innate predispositions could be observed at work in the brain.

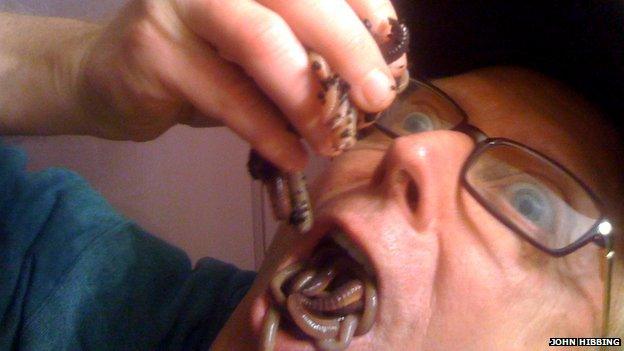

So they tested instinctive responses to images designed to provoke disgust and fear, and found a link between the strength of response to the pictures, and how socially conservative a person's views were likely to be.

"We need to make clear the distinction between economic conservatism and social conservatism," says Dr Hibbing.

"People who have more protective attitudes about things like immigration, who are more eager to punish criminals, people who oppose abortion... these are individuals who seem to have a much stronger reaction to disgusting images."

These reactions are measured biologically, so the studies are linking explicit, conscious opinions with subconscious responses.

In the research done so far, it's attitudes to risk, disgust and fear that show the strongest links to overt political views.

John Hibbing eating worms in a reconstruction of the kind of "disgusting" images used in his research

The difficulty comes when trying to apply these insights to a specific situation.

American social conservatives might also be strongly in favour of a smaller state and a freer market. In former Eastern bloc countries, social conservatism might make you more likely to hanker after the old days of Communism.

Behavioural economist Liam Delaney is studying the psychology of the Scottish independence referendum campaigns, but he warns against thinking that our subconscious instincts can be a complete guide to the debate.

"Biological determinism is a little tricky with these situations, because there's just too much variation across different political systems.

"So I think you'd risk simplifying things by saying that there is a hard-wire that's determining the outcome."

Darren Schreiber agrees: "Human politics is extraordinarily complex. It's not just reduced to brain, and I want to be very clear that I'm not a biological determinist. We're hardwired not to be hardwired.

"If people were simplistic we wouldn't need these very big, complex brains."

None of the scientists doing this research claims that our political views are completely innate.

Human brains change throughout our lives, so neuroscientists are careful to say that our experiences, as well as our genes, have shaped the brain they're putting in the scanner.

But John Hibbing believes our subconscious drives, which evolved long ago in response to urgent physical dangers, direct our political minds more than we like to think.

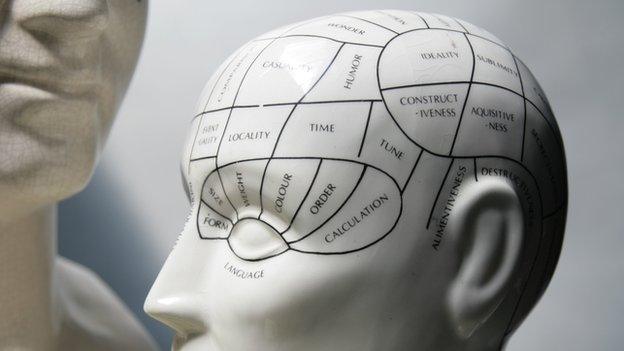

In the 19th Century people commonly used phrenology to map the brain, a since discredited scientific theory that linked particular parts of the head to character and personality

"People like to believe that their own political beliefs are rational, that they're a sensible response to the world around them, so when we come along and say, 'Maybe there are these predispositions, influential but perhaps not fully in your conscious awareness,' that's not the way we like to view our own political beliefs."

He compares our innate ideological tendencies to which hand we prefer to use. We used to think of this as a habit that could be changed, yet now know it to be "deeply embedded in biology".

That would have profound implications for political life. If being left-wing is as innate as being left-handed, why bother with politics at all?

Could we just put everybody in a brain scanner and infer what they think, and will always think, and were born to think, and stop trying to change anybody's mind?

I was relieved to find that even John Hibbing doesn't draw that conclusion. "It's not so much that I think people should just shut up and accept that some people are different. But I do think they should accept that some people are either not going to change or they're going to be extremely difficult to change, and that simply by continuing to shout at them, we're not contributing to anything."

So we won't be swapping the ballot box for the brain scanner, any time soon.

Which is good, because I still think politics should be about taking our ideas out into the world beyond our skulls, the real world of challenging beliefs and clashing opinions.

Perhaps I'm just hard-wired to think that way.

Listen to Personality Politics on BBC Radio 4 at 11:00 BST on Tuesday 20 May 2014.

- Published5 May 2014

- Published5 March 2013